Sara Sheehy worked in partnership with Visit Idaho to create this Travel Tip.

While there are far fewer sheep ranchers in Idaho now than there were in the early 1900s, the culture of sheepherding is still very much alive. Nowhere is this more evident than at Ketchum’s Trailing of the Sheep Festival, a three-day celebration of sheep ranching and sheepherding culture and history that takes place each fall.

But you don’t need to wait for the festival to catch a glimpse of this living culture and history. One adventurous way to explore the past is by seeking out Basque arborglyphs, a unique remnant left by the herders who spent long, quiet summers moving bands of sheep across Idaho’s landscapes. To learn more about these fleeting but poignant pieces of ranching history, I joined an arborglyph tour at the Trailing of the Sheep Festival last fall. Here’s what I learned.

What Are Basque Arborglyphs?

Basque Arborglyphs are carvings made in the bark of a living tree. They can be words, names, dates, drawings or any other type of marking. The carving is often done with a sharp knife into a tree with smooth bark, like an aspen, birch or beech tree.

When touring arborglyphs at the Trailing of the Sheep Festival, the focus is on markings carved by sheepherders in aspen trees as they “trailed” up and down the Wood River Valley, moving bands of sheep from one grazing spot to the next. Many of these arborglyphs were created by Basque herders who worked throughout this area in the early and mid-1900s.

Why Are Arborgylphs in Idaho?

The Basque are a people from the Pyrenees Mountains, located on the border of Spain and France. The Basque began traveling to the United States in the late 1800s, and many took positions as sheepherders in the American West, where a willingness to work independently and in isolation was more valuable than the ability to speak fluent English. Some worked in the area for just a few years, while others acquired their ranches and settled their families in the Wood River Valley.

In the heyday of sheep ranching in Idaho, herders also came from Scotland and Ireland. Most modern-day herders that you’ll find throughout the state are from Peru, Mexico, Chile and Mongolia.

What to Expect on the Arborglyph Hike

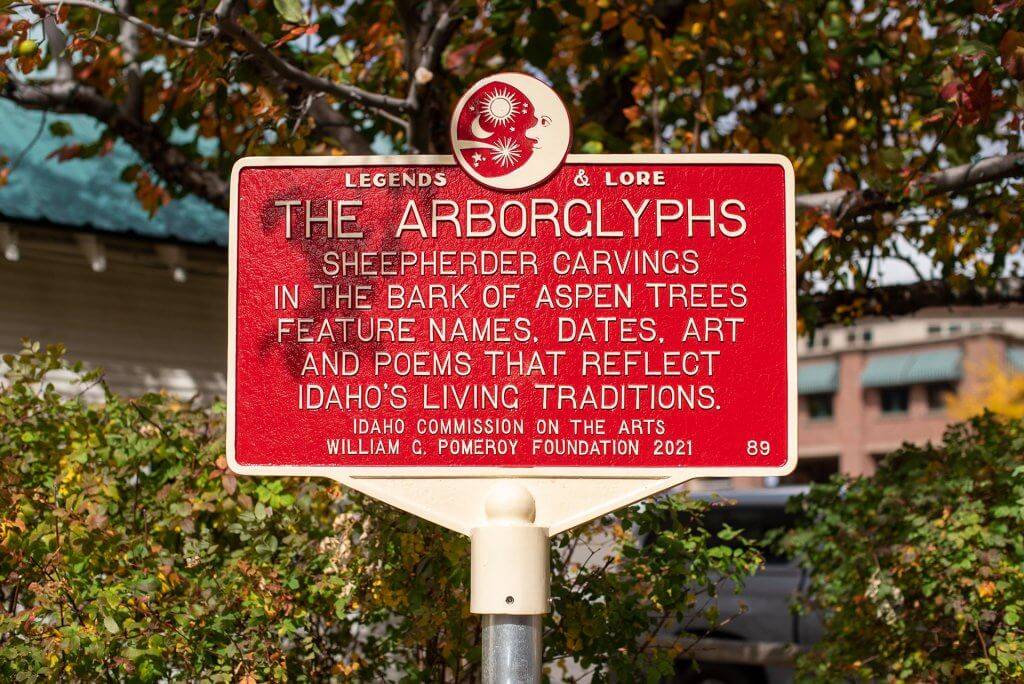

The arborglyph tour began with a meetup at Ketchum’s Forest Service Park, right next to a sign honoring the area’s sheepherding heritage. The sign reads, “The Arborglyphs: Sheepherder carvings in the bark of aspen trees feature names, dates, art and poems that reflect Idaho’s living traditions.”

Dozens of people gathered in the park, bundled up against the unseasonable chill. Soon, John Peavey joined us, along with local historian Jerry Sieffert. A third-generation sheep rancher and former Idaho State Senator, Peavey is soft-spoken; we all quieted and leaned in to hear his words. He shared directions to our destination—a small canyon called Neal, just north of Ketchum—and joked with Sieffert, getting the whole crowd laughing.

“I hope you aren’t disappointed,” he says, turning serious before we all piled into our vehicles. “The arborglyphs are disappearing.”

I thought about the ephemeral nature of arborglyphs as I followed Peavey’s truck north, my eyes catching on the shepherd’s crook he had tucked in his truck bed. We drove through a quiet neighborhood onto a dirt road, wet from the previous night’s rain. Peavey waited for us all to park and gather before he began speaking, telling us about how the evergreen trees in this particular canyon are shading out the aspen, causing the arborglyphs to disappear as the aspen dies.

This is one way that arborglyphs can be lost, but there are others as well. A tree can grow so big that the bark stretches, making the arborglyph unrecognizable. The tree can also be cut for firewood, or vandals can scratch over the historic carvings. But even if the arborglyph escapes those fates, eventually, the tree will die from old age. In the west, aspens in perfect growing conditions will live for about 150 years.

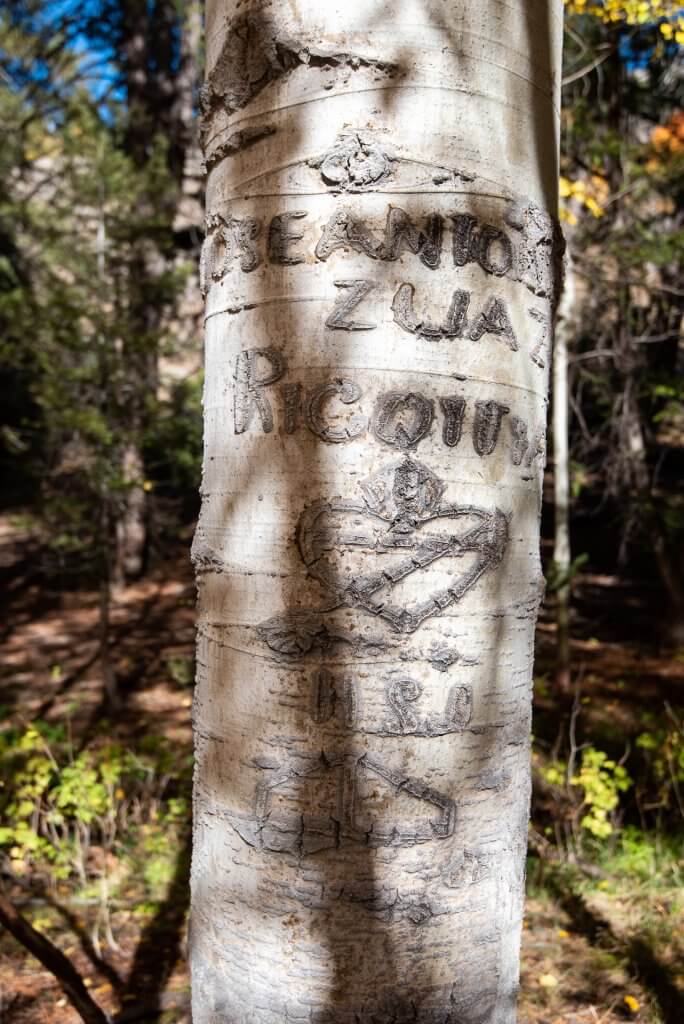

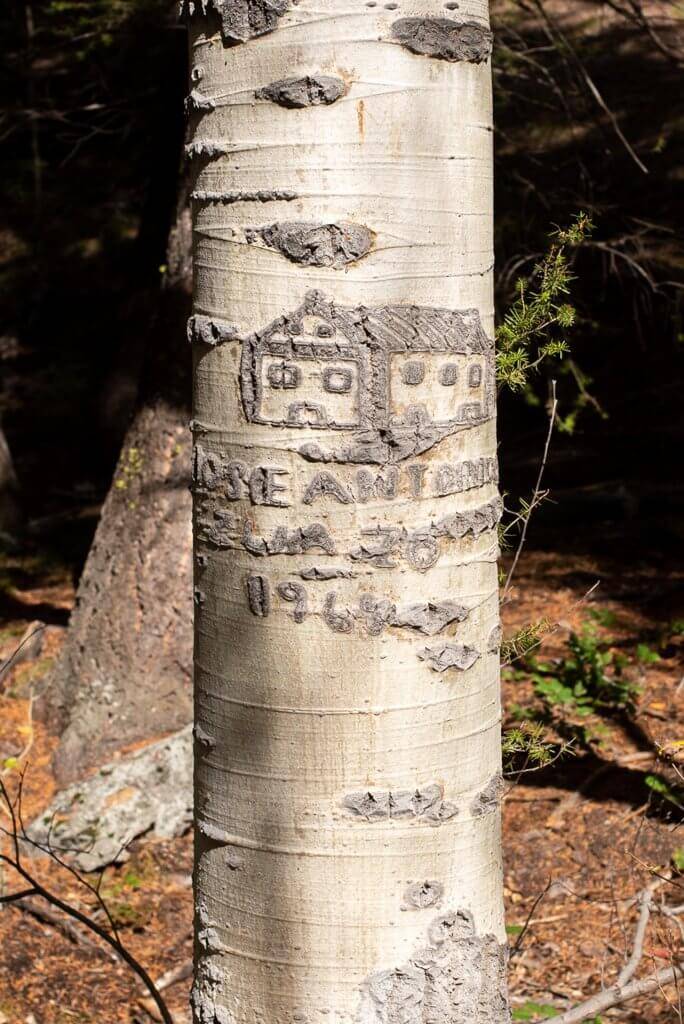

As we wandered through Neal Canyon, Peavey pointed out an elaborate carving of a Basque boarding house (boarding houses, like the Jacobs/Uberuaga House in Boise, served as a social center and community gathering point for Basques in the early 20th century), a heart topped with a crown, a sheep wagon and at least a dozen names and dates.

Some names were easy to read, like Jose Antonio Zuazo, who carved his name in 1969. “You’ll know by the name whether they were Basque or Peruvian,” Peavey shares as he runs his hand over Zuazo’s carving. “Most around here are Basque,” he adds. The last name Zuazo, which is indeed Basque in origin, loosely translates to “dweller at the abundance of trees or forest.” How fitting to have this name carved in this aspen grove for the past 50+ years.

Peavey ended the tour by answering questions about sheep ranching and how it has shifted and changed over the generations. Though the Wood River Valley was once the world’s second-largest producer of lamb, it is now home to just a handful of sheep ranching families. These days, sheep wagons are pulled by a truck instead of a horse, and you’re more likely to find a herder catching up on Netflix in the quiet heat of the day than carving a memento in an aspen tree.

Even so, many things stay the same. Ranchers still work hard to scrape a living out of this sometimes unforgiving land, and herders still travel from other countries to care for the bands of sheep as they move across the landscape, grazing on mountain hillsides. And, for now, we have these arborglyphs to remind us how long these traditions have been in place.

Where to Find Arborglyphs on Your Own

Though the arborglyph tour at the Trailing of the Sheep Festival only happens once a year, you can seek out these fleeting reminders of the past on your own. There is no centralized database of existing arborglyphs to reference, but you can find them with a few tips and a sense of adventure.

According to Peavey, arborglyphs can be found throughout the Wood River Valley. Sheep camps usually need to be accessible by road to move the wagon from place to place, so dirt roads that reach into public lands, like Eagle Creek and Lake Creek north of Ketchum, are good places to start. Camps also need to have a water source, like a creek or river, and enough downed trees to supply the herder’s campfire.

“This is an ideal place,” Peavey explains, gesturing to the small stream and plentiful downed trees in Neal Canyon.

Arborglyphs can also be seen elsewhere in Idaho, including in the Boise National Forest. Wherever there is a history of sheep ranching and grazing and a shady place for herders to escape from the heat of a summer afternoon, you’re likely to find these carved pieces of history.

There’s so much to explore at the Trailing of the Sheep Festival. Dig into this festival guide to plan your trip.

Feature image credited to Sara Sheehy.

Sara Sheehy is a writer and photographer who travels the world seeking wild places and great stories. When she’s not on the road, Sara spends her time exploring the mountains.

Updated on September 13, 2023

Published on September 27, 2022