This is a sponsored post.

I’m lying on my inflatable camp mattress, afloat in a pool of warmth waiting for the stars to illuminate the evening sky. Thirty miles north of McCall, Idaho, the light pollution is all but gone. And so is the audible hustle and bustle of city life. The silence is broken by my travel partner, Chris Minson, who is floating a few feet away when he stutters “…this was a very good idea.”

Minson and I catch up yearly to adventure together. Last year we skied around Washington’s Mount Rainier—a colossal effort that kept us in an icebox while orbiting the peak over 5 days. This year’s plan was to tackle a 200-mile section of the Idaho Hot Springs Mountain Bike Route. Floating in 100˚ F mineral water, it was literally the polar opposite of our dismal icy shenanigans … the hot springs were a good idea indeed.

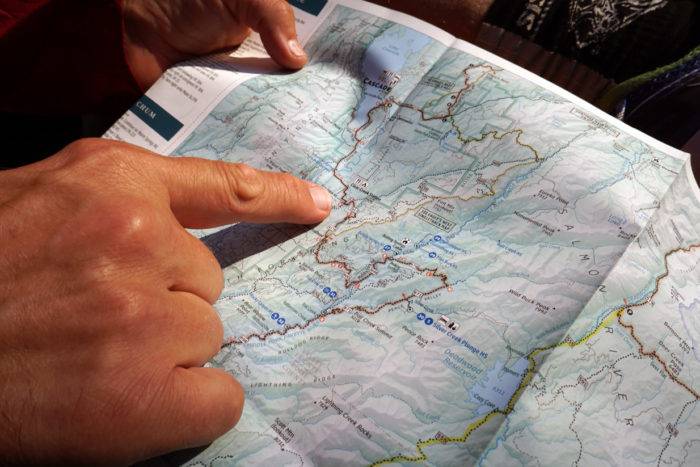

An official cycling route, the Idaho Hot Spring Mountain Bike Route (IHSMR ) is the brainchild of Casey Greene, a cartographer with Adventure Cycling. Greene reads maps like you and I read the paper. Topographic lines and rivers are punctuated with trails and roads, revealing a story for Greene. And if you should know anything about Greene, he’s got a little thing for hot springs (and fire towers, but that’s a different story, one which I encourage you to dig up). Greene spent the better portion of two summers in the saddle, ground truthing a route that would connect 50 of Idaho’s hot springs by bike, looping Boise to Ketchum to Stanley to McCall and back.

In 2014 Greene published two Idaho hot spring maps with Adventure Cycling, the Main Route (mapping 500+ miles of gravel and tarmac) and the Singletrack Option (150+ miles of rideable trail), detailing the elevation profile, mileage, history and resupply options along the way. It’s a beautiful infographic showcasing the potential for adventure.

With a pocket full of days, we headed north poised to tackle the west arm of the route, riding from Burgdorf to Idaho City, hitting a new spring each day.

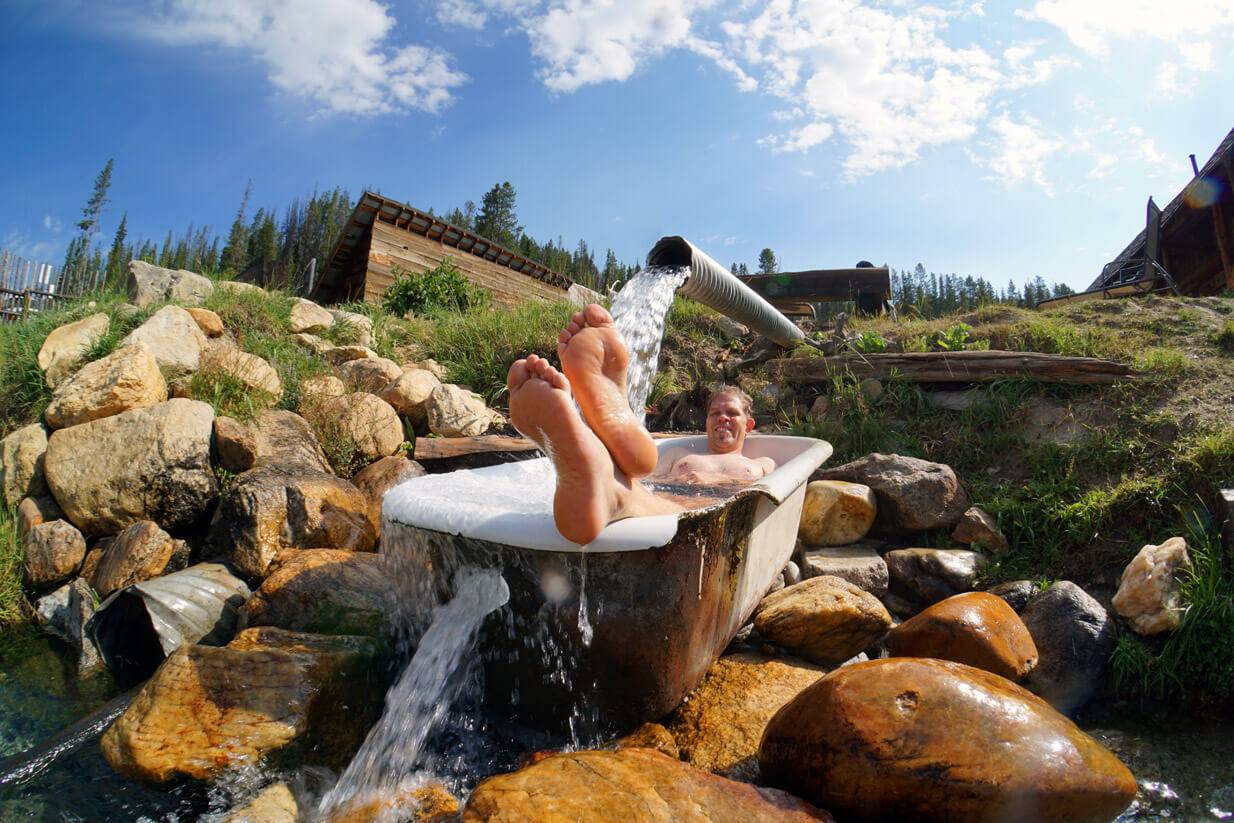

Teetering at the edge of modern society, Burgdorf is a shadow of a mining town that hasn’t changed much since it was founded in the 1860’s. At the turn of the century, miners would come to soak their weary bones for two bits. These days visitors can take a day trip out of McCall on Warren Wagon Road and soak for $8 ($5 for kids), or rent one of the 16 shambling cabins slumped on the hillside above the pool for $50/person per night.

We chose to rent a cabin to use as our basecamp, spread out the gear and prep the rigs for the anticipated ride. The Hilton it is not—no electricity, no refrigerator—fifty bucks a head gets you a bed, a stove, a table and porch…and 24-hour access to the pool…priceless.

Because the only road to Burgdorf is paved, it’s not part of the Main Route. Instead, Greene linked miles of trail and published it on his Singletrack Option as a northern extension looping deep into the Payette National Forest. Interested in covering miles rather than wrestling bloated bikes over rugged trails, we opted to take Warren Wagon road into town.

Bags packed, bikes ready, we were lured back into the pool for “one more soak” before we burned through the 30 miles of lonely tarmac south into McCall.

Our ride had dual purpose: ride, soak and repeat. To that end, we mapped a route that would put around 50 miles in the saddle between hot springs and a guaranteed soak at the end of the day. From McCall, the Main Route took us east of Highway 55 on Farm to Market Road and then ducked east on gravel roads towards Gold Fork Hot Springs.

Gold Fork is the antithesis of Burgdorf. Both springs are spectacular, but each in their own way. Burgdorf is old and rustic, bound by hand hewn logs while Gold Fork is gussied up with travertine tiled pools that cascade the 113˚ F spring through a series of pools that eventually drain out at a pleasant 70˚ F at its lowest point.

We met a husband-wife mining team who work the hills out of Placerville that put it best, “You bring your family to Gold Fork, but bring your honey to Burgdorf!” Indeed, we rolled into the Gold Fork parking lot around 4 p.m. to a gaggle of kids and families with coolers and pizza boxes.

For those looking to make Gold Fork a formal stop, it warrants noting that Gold Fork has no (official) water source, offers limited supplies and does not offer much in the way of camping. The Gold Fork yurt sells a few candy bars, bottled water and soda for a buck. We filled our water bottles directly from the hot spring – yes, hot! But yes, potable (mind the slight smell of sulfur).

Most of the adjacent land is private and regularly monitored to keep individuals from setting up camp. Pedal four miles up the road, cross the bridge and you’ll find established campgrounds on public land.

If you’re waffling on which direction to tackle the west arm (south to north, or north to south), this section will make you a believer in starting from the north. Gold Fork to Cascade climbs (and descends) 2,000’, but is much steeper when approached from Cascade. Whipping off the mountain, we pedaled easy miles in and out of Cascade along a spectacular swath of country road, shadowed by the mountains to the west. We eventually pulled across Highway 55 and climbed high into the Boise National Forest.

And if the descent off Eagle’s Nest wasn’t impressive enough, the descent into the Middle Fork of the Payette River is hold-on-tight-type of fun. After rolling across the summit ridge for a handful of miles, we bombed down the gravel road for a good 30 minutes before spilling out into the stunningly beautiful Middle Fork basin, a spectacular drainage so rich in hydrothermal activity that two resorts have ‘sprung’ up, making a business out of hot springs.

We opted for a more dirt-under-the-nails type experience and set up camp at the Boiling Springs campground where $15 gets you a permit, hand pump well access, a picnic table, fire pit and access to a vault toilet. Though there are a number of places fit for the feral, if you wanted to really do it up right, the savvy camper would reserve the Boiling Springs cabin ($55/night) six months in advance.

True to its name, Boiling Springs was indeed too hot to take a dip and with the nearby Moondipper hot springs (reputed as one of Idaho’s best), throngs of visitors were siphoned from the trailhead to make the trek to the springs. Knackered, we simply followed the Boiling Springs drainage to the river where someone had dug out a fine pool with a diversion stream from the river to adjust the temperature. We had the off-the-map spring all to ourselves and soaked late into the night.

August in Idaho can be downright hot as Hades. We were blessed with cooler temperatures and first light brought a fleeting summer storm that tempered the dust and allowed us to make quick work of the next 25 miles into town. After a quick hour in on the bike, we saddled up to the Two Rivers Restaurant in Crouch for not one, but two breakfasts each. Two days of solid riding has its rewards!

From Crouch, the 13-mile climb to Placerville started out gradually but chased to the sky with a final grunt to the summit pass. A quick descent rolled us out into the semi-ghost town which used to sport three bars and a mercantile. One bar has been converted to a pioneer museum managed by a gentleman who weaves expletives like an art form. Stop by Donna’s, an authentic mercantile, for a cold soda or an ice pop. Sweet water bubbles up from a natural spring out back of town.

Onward to Idaho City, the last stop on our hot spring route would be The Springs Resort. Back in the day, it’s said that Idaho City pulled more gold out of the hills than Alaska and California combined. Some of the original buildings still line the quiet streets, but nowadays Idaho City ekes out an existence primarily on servicing ATV and hunting tourism.

The Warm Springs Resort originally opened in 1862, but was closed for some time before new owners revived the hot water under the new name, The Springs. Nearly $3 million dollars have recently been invested updating The Springs, giving it a true resort-like experience.

Hot off the trail, The Springs greeted us to a spa-like environment. A bevy of food and drink and even a massage were available if you want it. We were each given a locker which included a towel and plastic bag (for wet trunks), washed off the miles of dirt and grime, walked out onto the partially shaded deck, propped up the waiter tab and waited for our ride back to town.

Hot springs and mountain biking are like cookies and milk. They just go together. We bookended our ride with some of the finest pools Idaho has to offer. But when asked about our favorite? Honestly, it’s the one we ended up soaking in after a hard day on the trail. So if you find yourself saddled up in the middle of nowhere, it might do you well to bring some trunks and a towel. Because there’s really no greater pleasure than recapping the day’s effort from the comfort of a natural hot spring. It’s a very good idea indeed.

Do It Now

Maps

While some Idaho bike shops may have the twin map set, log onto Adventure Cycling Association to purchase the maps for $15.75 each. Click here to preview the full map.

The Bike

We each rode bikes designed for two different experiences. Chris rode a full suspension mountain bike designed for downhill riding. I chose to ride a more gravel-centric ‘adventure bike’, designed for long miles on fire roads. In the end, “ride the bike you brung”.

Carrying supplies

Long gone are the days of panniers and bloated cargo trailers. If you are tackling the route on a mountain bike—or any bike—consider purchasing bike frame bags. The bags take advantage of otherwise empty spaces, carrying supplies inside the frame’s triangle, lashed to the handlebars, and off the seat post. Bags travel tight and keep the bike balanced well. You’ll likely still need a backpack, but the seasoned cyclist will put light and puffy gear in the pack to keep the weight off the seat bones. Instead, slip that 6lbs of water in a frame bag.

Resupply

Supplies can be purchased in McCall, Donnelly, Cascade, Crouch, Garden Valley, Idaho City, Boise, and to a lesser extent Roseberry and Placerville. We chose to divide the route into 50-60 mile intervals, which when starting from Bergdorf, will put you roughly in the middle of nowhere each night. So be prepared to eat well before you head into the hot springs and have a light dinner … or bring a stove to cook a meal on the road. For this section of the route, I would recommend carrying two dehydrated dinners.

Water

The west arm of IHSMR route parallels several rivers and passes through enough towns to keep you hydrated. We each brought a 3L bladder and one or two water bottles. While we brought water purification, we didn’t use it.

Fire

The beauty of the route is that it travels on perfectly groomed, not too steep, not too soft, dare I say ‘world-class’ backcountry gravel roads. These roads were purpose built – to provide quick access to the backcountry in case of a wildfire. Indeed, at the time of our trip, we had not one, but two fires, including the (as of now) 63,000-acre Pioneer Fire of 2016. Our route skirted west of the blaze. With fires in mind, the route is probably best tackled in June, after the snow melts and before the fires start. But be sure to check in from time to time while on the route to ensure you are traveling into fire free zones.

Training

Riding a bike for 200 miles can be daunting. But the elevation profile on the route isn’t wildly outrageous. Our longest day, we climbed 5,000 feet. With a loaded bike, it’s a patient 5,000 feet. So it’s important to toughen the legs to endure moving 5-6 hours at a time. To get ready, take a few long rides in advance. Even better, load the bike and take a few long rides. If you can, find a long hill to climb—a climb that takes an hour or more to get to the top. One long ride a week plus a handful of other rides will get you there.

Gear

Space is the final frontier of bike packing. For ideas on maximizing the space to weight ratio, look at the bike packing brethren, the light weight backpacker. Ultralight weight backpackers have dialed in how to go fast and light and have blogged volumes on the subject.

All photos, including feature image, are credited to Steve Graepel. Additional images credited to co-photographer Chris Minson.

Artist, writer, adventurer, father of two, Steve Graepel is in constant pursuit of the balanced life. Living in Idaho, he can pursue it with gusto. Steve’s work has appeared in National Geographic Adventure, Patagonia’s The Cleanest Line andGearjunkie.com.

Steve and his wife Kelly live in Boise, Idaho with their two children, Chloe and Ethan.

Published on September 8, 2016